Is It Possible to Put an End to Wars? Einstein and Freud Discuss It in These Letters

Long before getting involved in developing the atomic bomb, Einstein debated with Freud over the war and its atavistic relationship with human beings.

In the 1930s, Albert Einstein lived in a time of deep doubts over the situation of the world and humanity amidst a world war. By that time, the political environment was tense and the ghost of war was also agitated. He had been chosen by the League of Nations to form part of the International Committee on Intellectual Cooperation, for which the objective was to gather scientists, researchers, philosophers, and thinkers in general whose work could provide solutions in the pursuit of peace. To participate in this debate, Einstein chose to correspond with Sigmund Freud for an external opinion that would be different than his and would allow him to better clarify his ideas in that regard.

One thing that stood out in their missives was the clear contrast between science and psychoanalysis when considering the problem of war. The naivety with which Einstein regarded certain aspects of the matter clashed head-on with Freud’s aplomb ––as if where one was allowed to dream about a world government comprised of the world’s best intellectuals, the other replied with the weight of an evident, if atavistic, reality. Unlike Einstein, Freud believed that war was the expression of an instinct, and therefore its eradication was practically impossible.

What is needed to distance humanity from the threat of war? That was the question that the scientist and the psychoanalyst set out to answer together. For Freud, the origin of the problem of violence lied in the dichotomy of power and law, and especially in the exercise of the former as a recurring method to solve a conflict of interest––At least until the time when law became the “power of the community;” the resistance of some against the powerful. From within that dialectics a paradox was born: according to some historical examples such as pax romana or the development of France as a country under the Capetian dynasty, war can be a means for peace; “it can serve to pave the way,” Freud wrote to Einstein. In this sense, the psychoanalyst agreed with Einstein on the suggestion of a collegiate government body that would resolve those conflicts of interest which, in the end, are the reasons for war.

With all of that, Freud also provided a psychoanalyst’s interpretation of war — he saw in it a manifestation of the destructive, consustantial impulse of human beings — Thanatos in a permanent battle with Eros — death trying to overcome Love, but not in a moral sense of goodness and evil, but in a human sense, in which at times, as individuals, death becomes an unexpected reason for force and vitality. This also makes it hard to think about a possible eradication of that conflictive side of the human being.

Will war ever end? In 1932, when Einstein and Freud were corresponding, neither offered the other a convincing argument; rather, they concluded on the desire of a future where bellicosity wasn’t the normal way to settle a dispute between conflicting interests. However, when their intellectual trajectories addressed this problem they left clues, suggestions whereby to continue to address this at least in our own scope of action and within our everyday life.

Related Articles

7 Recommendations for Organizing Your Library

For the true bibliophile, few things are more important than finding a book from within your library.

Red tea, the best antioxidant beverage on earth

Red tea is considered to be the most unusual of teas because it implies a consistently different preparation process. ––It is believed that its finding came upon surprisingly when traditional green

A brief and fascinating tour of the world's sands

To see a World in a Grain of Sand And a Heaven in a Wild Flower, Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand And Eternity in an hour. - William Blake What are we standing on? The ground beneath our feet

Strengthen your memory with rosemary oil

For thousands of years rosemary oil has been traditionally admired and used due to its many properties. In the Roman culture, for example, it was used for several purposes, among them cleansing, as

Literature as a Tool to Build Realities

Alain de Botton argues that great writers are like lenses through which we can see an infinite array of possibilities.

Mandelbrot and Fractals: Different Ways of Perceiving Space

Mathematics has always placed a greater emphasis on algebra, a “purer” version of itself, one that is more rational at least. Perhaps like in philosophy, the use of a large number knotted concepts in

Luis Buñuel’s Perfect Dry Martini

The drums of Calanda accompanied Luis Buñuel throughout his life. In his invaluable memoirs, published under the Buñuel-esque title, My Last Sigh, an entire chapter is dedicated to describing a

A Brief Manual of Skepticism, Courtesy of Carl Sagan

Whether or not you’re dedicated to science, these tips to identify fallacies apply to any form of rigorous thinking.

How to Evolve from Sadness

Rainer Maria Rilke explored the possible transformations that sadness can trigger in human beings.

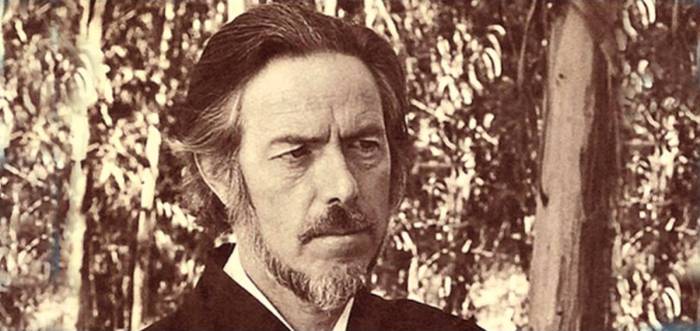

Alan Watts, A Discreet And Charming Philosopher Of The Spirit

British thinker Alan Watts was one of the most accessible and entertaining Western interpreters of Oriental philosophy there have been.