Structures That Meditate: The Beauty of Japanese Carpentry

Traditional Japanese carpenters aspire to making the spirit of a tree immortal in an everlasting structure.

Like all of us, trees will end up as dust. But there is the possibility of interrupting that process and do something with a tree that will allow it to continue to exist and have a second life. Traditional Japanese carpenters aspire to that ––to capture the spirit of a tree in a piece that, as well as being an object of beauty, will last forever.

If a tree has had an enjoyable life it expresses it in its fibers, says George Nakashima, acknowledged as one of the world’s foremost master carpenters and, according to the Japanese government, “the carrier of a sacred secret.” Nakashima believes, as the druids did, that each tree has a ghost inside and that the carpenter must know it and make it last. The more years and the better conditions the tree has lived, the better it will be for transforming its spirit into a beautiful object. For that reason, all woodwork in Japan is one-on-one –man to trunk – and never with metal or iron, which would prevent them from bonding. The tools used by the master carpenter are limited to chisels (nomi), hammers (mokuzuchi), saws (nokogiri) and brushes (kanna).

For many, the charm of Japanese carpentry lies in the fact that it reminds them of the ancient world of handcrafts, a now-extinct era that was in harmony with nature through the careful observation of its cycles and rhythms. For others it is the esthetic of the assembly, whose technique comes precisely from that observation of the natural rhythms presented by the geometric union, often invisible, of all the parts. The system of interlocking that connects the wood via complex and self-sustainable joints was already a widely used skill when the Miya-Daiku built their famous Zen temples and teahouses.

Nakashima, the grandson of a samurai warrior, was one of the more modern practitioners of this technique and he brought it to the West. He saw his skill as a kind of spiritual occupation that transformed the beauty of a tree into functional art. His work ethic can be summarized in his final comments of The Soul of a Tree:

I have a one-man war against modern art, for instance. It’s the predominance of a personal ego that bothers me. My ideal is that a craftsman should be unknown rather than known. He doesn’t have to throw his ego around. This goes back to other civilizations. For instance, in the Sung Dynasty in China, the craftsman never signed his pieces. I think that’s indicative of a healthy civilization. Everything that they produced was worthy, artful, beautiful.

Japanese carpentry conserves the singularity of each one of its master craftsmen and, according to them, also conserves the spirit of the tree that spawned each piece. But all of the transmigrations that occur in the creative process belong to a subtle and discreet world, similar to the invisible joints in furniture or houses where what is important is beauty, strength and the long-lasting quality of a tree that otherwise would have died.

The invisible assembly seen in the modern world represents the survival of an art form that directly imitates the discretion and phantasmagorical geometry of nature. A work that is carried out almost psychically with the wood. It is not the interest in the piece of furniture itself that is important (a master craftsman would hardly design a plastic chair), but what matters is a good piece that appears to be meditating in place.

Related Articles

Pictorial spiritism (a woman's drawings guided by a spirit)

There are numerous examples in the history of self-taught artists which suggest an interrogation of that which we take for granted within the universe of art. Such was the case with figures like

Astounding fairytale illustrations from Japan

Fairy tales tribal stories— are more than childish tales. Such fictions, the characters of which inhabit our earliest memories, aren’t just literary works with an aesthetic and pleasant purpose. They

A cinematic poem and an ode to water: its rhythms, shapes and textures

Here lies One Whose Name was writ in Water. - John Keats Without water the equation of life, at least life as we know it, would be impossible. A growing hypothesis holds that water, including the

Watch beauty unfold through science in this "ode to a flower" (video)

The study of the microscopic is one of the richest, most aesthetic methods of understanding the world. Lucky is the scientist who, upon seeing something beautiful, is able to see all of the tiny

To invent those we love or to see them as they are? Love in two of the movies' favorite scenes

So much has been said already, of “love” that it’s difficult to add anything, much less something new. It’s possible, though, perhaps because even if you try to pass through the sieve of all our

This app allows you to find and preserve ancient typographies

Most people, even those who are far removed from the world of design, are familiar with some type of typography and its ability to transform any text, help out dyslexics or stretch an eight page paper

The secrets of the mind-body connection

For decades medical research has recognized the existence of the placebo effect — in which the assumption that a medication will help produces actual physical improvements. In addition to this, a

The sea as infinite laboratory

Much of our thinking on the shape of the world and the universe derives from the way scientists and artists have approached these topics over time. Our fascination with the mysteries of the

Sharing and collaborating - natural movements of the creative being

We might sometimes think that artistic or creative activity is, in essence, individualistic. The Genesis of Judeo-Christian tradition portrays a God whose decision to create the world is as vehement

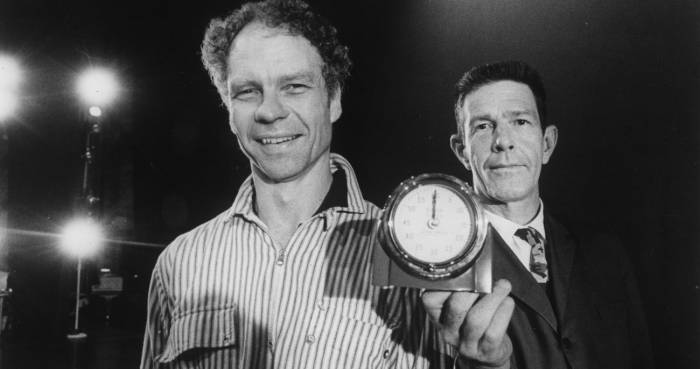

John Malkovich becomes David Lynch (and other characters)

John Malkovich and David Lynch are, respectively, the actor and film director who’ve implicitly or explicitly addressed the issues of identity and its porous barriers through numerous projects. Now