What Are the Best Movie Soundtracks of All Time? (I/II)

The mutual and symbiotic influx between image and sound is confirmed by these twenty-two unforgettable soundtracks.

Musical scores for the big screen, rich enough to be considered complete works in themselves, have been recorded throughout history. Some more, others less, restore film’s oneiric capacity to balance, consciously, the viewer’s unconscious—that which does not just look at the screen but also listens to it.

Below we present the first half of a list containing some of the most brilliant movie soundtracks of all time.

Paris, Texas (Wim Wenders, 1984) — Possessed by the deserted landscapes of Travis Henderson’s (Harry Dean Stanton) soul, Ry Cooder’s guitar weeps for the intimate scenes that comprise this resurrection journey. Wenders already had some experience in the road movie genre, but with the help of this soundtrack he establishes himself as one of the classics of global film.

Ascenseur pour l’échafaud (Louis Malle, 1957) — Due to his boldness in involving young Miles Davies in the creation of the musical themes for this enigmatic female Film Noir —parallel to the Nouvelle Vague—, today we can delight in the finest jazz that took shape after be-bop. On this occasion, Davis found his band and a new way of making jazz, which would later influence him in the creation of masterpieces such as Kind of Blue. Ascenseur pour l’échafaud’s album, which lasts half an hour, can be listened to independently from the film, delighting people who enjoy jazz and as well as those who don’t. It works flawlessly with the images, however, and it is also an important narrative component for Jeanne Moreau’s dialogues and the plot’s suspense.

La Planete Sauvage (René Laloux, 1973) —This wonderful animated science fiction film, which includes hypnotic illustrations by Roland Topor, is complemented by Alain Goraguer’s music, which ends by bestowing it with a magical character. As the plot develops, we find out that humankind is possessed by a superior alien race, and thanks to Terro’s prowess, humans can be freed. The music places us in a timeless universe, quicksand for any action, liquid memory for events that are yet to come.

The Wizard of Oz (Victor Fleming, 1939) —There is music created for films that forms our mind, dimensions it and limits it. Such is the case of this soundtrack, in which Judy Garland vocalized the American Dream, becoming Dorothy to realize that no magical place is better than the mere reality of the individual who lives his life, even if this is in Kansas.

The Piano (Jane Campion, 1993) — English composer Michael Nyman —linked to minimalism but of a baroque nature— developed a supremely personal style that is recognized primarily in the director Peter Greenway’s work, many of which he endowed with a unique character. In turn, in The Piano, a film in the peak of director Jane Campion, the music impresses a particular seal while it simultaneously becomes the object around which the entire plot revolves. The central dramatic object is a piano, an outlet for a character who cannot speak; the soundtrack is that which the character interprets and through the music we develop a particular empathy with Ada (Holly Hunter). The album is yet another example of the musical works that can be composed under the excuse of making a film, and which people who have not seen the film can enjoy, and surely then seek out the film.

Blue Velvet (David Lynch, 1986) — Probably the best example of the vast collaboration between Angelo Badalamenti and Lynch, in the same nostalgic nature of strings as dark as the wings of an angel in a starless night. Accompanied by three classical tracks that contextualize the film, as well as planning it as a metaphorical reflection on the American nightmare. Love Letters by Ketty Lester, Honky Tonk by Bill Doggett, In Dreams by Roy Orbison (particularly used in an amazing manner). It also includes a song by contemporary singer Julee Cruise, whose voice is the perfect bridge between Badalamenti and Lynch.

Secondary Effects (Steven Soderbergh, 2013) — Thomas Newman helped Steven Soderbergh’s opera prima —Sex, Lies and Videotape (1989)— have the archetypal resonance that characterizes it. Many years later, in Secondary Effects, his talent, magical and melancholic, becomes a pill that seems to alleviate our depression, although it actually only increases it.

Breaking and Entering (Anthony Minghella, 2006) — The fantastic electronic band Underworld joins forces with Gabriel Yared to create this plate of atmospheric proportions, delicate melodies that comprise a type of progressive minimalism, typical of postmodernity’s conflicts.

Lost (David Fincher, 2014) — Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross won an Oscar for the soundtrack of the Social Network (David Fincher, 2010), a musical score that better than the film elaborates the lucubration surrounding the nature of a social network. This could be the soundtrack of the globalized age, a world completely dependent on cyberspace. In the chronological construction of sequences, in the shape of leitmotifs, the music supports the tricky plot that until the final plane plays with our assumptions. The music, however, can also be listened to independently from the film: it bestows the space where it is reproduced with depth and textures, as if it opened a window to another time taking place in our ears.

The Last Emperor (Bernardo Bertolucci, 1987) — Ryuchi Sakamoto is the film’s main composer: his emotive compositions are complemented by the images, reminding us that film can be seen as a sacred act in the viewer’s eyes. The soundtrack also includes scores by David Byrne, which use traditional instruments from the Orient, incidentally though, which gives clarity to the soundtrack while it also contrasts with Sakamoto’s solemn style. Lastly, Cong Su’s composition, which does include traditional instruments as its base, gives the film a period touch, since it corresponds entirely with the scenes from the emperor’s childhood. In sum, the combination of Sakamoto-Byrne-Su results in a perfect balance for this historical piece.

Blade Runner (Ridlley Scott, 1982) — This selection would not be complete without Vangelis who, with 1930s-1940s salon music, complemented Scott’s adaptation of the Noir soul of Phillip K. Dick’s novel. Now, perhaps because it foresaw events that were to come, that music can sound as new as it did when it accompanied the film’s premiere.

The Remains of the Day (James Ivory, 1993) —The masterpiece by elegant James Ivory (an adaptation of Kazuo Ishiguro’s novel), demanded all the neatness that the composer and the interpreters could muster. Richard Robbins accomplished this, with certain closeness to Gustav Mahler, without forgetting that, after all, music has a secondary role in film.

Related Articles

Pictorial spiritism (a woman's drawings guided by a spirit)

There are numerous examples in the history of self-taught artists which suggest an interrogation of that which we take for granted within the universe of art. Such was the case with figures like

Astounding fairytale illustrations from Japan

Fairy tales tribal stories— are more than childish tales. Such fictions, the characters of which inhabit our earliest memories, aren’t just literary works with an aesthetic and pleasant purpose. They

A cinematic poem and an ode to water: its rhythms, shapes and textures

Here lies One Whose Name was writ in Water. - John Keats Without water the equation of life, at least life as we know it, would be impossible. A growing hypothesis holds that water, including the

Watch beauty unfold through science in this "ode to a flower" (video)

The study of the microscopic is one of the richest, most aesthetic methods of understanding the world. Lucky is the scientist who, upon seeing something beautiful, is able to see all of the tiny

To invent those we love or to see them as they are? Love in two of the movies' favorite scenes

So much has been said already, of “love” that it’s difficult to add anything, much less something new. It’s possible, though, perhaps because even if you try to pass through the sieve of all our

This app allows you to find and preserve ancient typographies

Most people, even those who are far removed from the world of design, are familiar with some type of typography and its ability to transform any text, help out dyslexics or stretch an eight page paper

The secrets of the mind-body connection

For decades medical research has recognized the existence of the placebo effect — in which the assumption that a medication will help produces actual physical improvements. In addition to this, a

The sea as infinite laboratory

Much of our thinking on the shape of the world and the universe derives from the way scientists and artists have approached these topics over time. Our fascination with the mysteries of the

Sharing and collaborating - natural movements of the creative being

We might sometimes think that artistic or creative activity is, in essence, individualistic. The Genesis of Judeo-Christian tradition portrays a God whose decision to create the world is as vehement

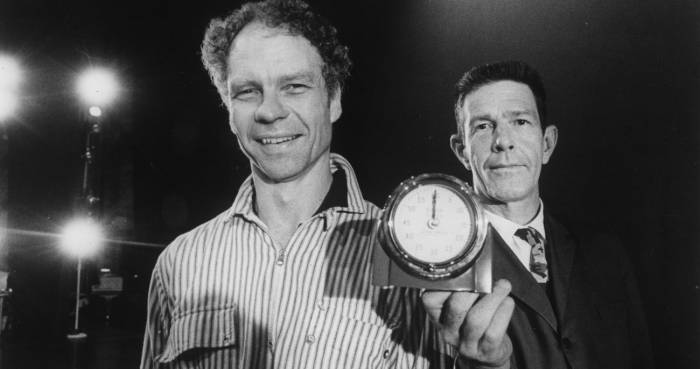

John Malkovich becomes David Lynch (and other characters)

John Malkovich and David Lynch are, respectively, the actor and film director who’ve implicitly or explicitly addressed the issues of identity and its porous barriers through numerous projects. Now