Tracing Back Our Obsession with Maps

From Ptolemy to Dawkins a brief explanation as to how cartography has fascinated humanity.

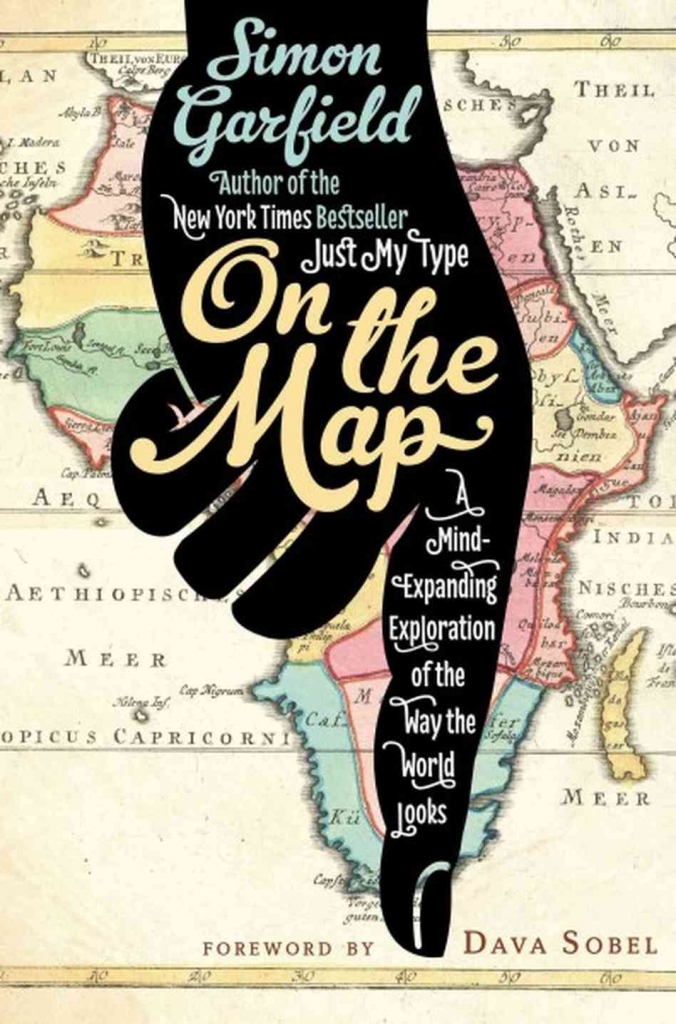

Throughout history we have employed cartography as a visual metaphor, a scientific explanation and a work of art. But, how exactly did maps come to play a central role in our lives? In On the Map: A Mind Expanding Exploration of the Way the World Looks, Simon Garfield explores our cartographic obsession from the classic era with Claudius Ptolemy through to post-modernist age with GPS and Google Maps.

Ptolomy’s Geographia … was a two-part interpretation of the world, the first consisting of his methodology, the second of a huge list of names and cities and other locations, each with a coordinate. If the maps in a modern-day atlas were described rather than drawn they would look something like Ptolemy’s work, a laborious and exhausting undertaking, but one based on what we would now regard as a blindingly simple grid system.

Ptolemy’s influence was enormous. But just as anything ever made by men, his view was completely determined by the political system of the time:

As one would expect, Ptolemy had a skewed vision of the world. But while the distortion of Africa and India are extreme, and the Mediterranean is too vast, the placement of cities and countries within the Greco-Roman empire is far more accurate. Ptolemy offered his readers two possible cylindrical projections —the attempt to project the information from a three-dimensional sphere onto a two-dimensional plane — one ‘inferior and easier’ and one ‘superior and more troublesome.’

One of the most interesting qualities of the Greek thinker was that, beyond the politicization of his mapamundi he took advantage of the situation by imagining and speculating about the places and countries which had not yet been discovered –– a deed that would influence the navigational routes of future adventurers and travellers.

Where earlier cartographers were willing to leave blanks on the map where their knowledge failed, Ptolemy could not resist filling such empty spaces with theoretical conceptions. … [T]his had the uncanny ability to send ambitious sailors, Columbus among them, to places they had no intention of seeing.

But instead of the proliferation of mapamundis one would expect after such wonderful work, the world descended for a 1000 years into what Garfield calls the ‘dark ages of cartography’. It was only until the rediscovery of the Ptolomy’s Atlas in its Latin translation in Venice (1950) that a modern appreciation of cartography was born, and alongside it our obsession with maps.

Garfield goes as far as to suggest (in accordance with Dawkins) that the elaboration of maps is a dividing line between monkeys and humans; a missing link of sorts. “Could it have been that drawing maps was what threw our ancestors beyond the critical portal that monkeys were not able to change?”, inquires Dawkins.

After the fascinating exploration of our global visualisation of the world, Garfield explores the ‘torrid romance’ that modernity engages with maps, highlighting the manner in which humankind has come to carry maps of the world to draw imaginary lines and divisions containing a large amount of the sense of life. ––A truly captivating concept, worthwhile of our time and attention.

Related Articles

Pictorial spiritism (a woman's drawings guided by a spirit)

There are numerous examples in the history of self-taught artists which suggest an interrogation of that which we take for granted within the universe of art. Such was the case with figures like

Astounding fairytale illustrations from Japan

Fairy tales tribal stories— are more than childish tales. Such fictions, the characters of which inhabit our earliest memories, aren’t just literary works with an aesthetic and pleasant purpose. They

A cinematic poem and an ode to water: its rhythms, shapes and textures

Here lies One Whose Name was writ in Water. - John Keats Without water the equation of life, at least life as we know it, would be impossible. A growing hypothesis holds that water, including the

Watch beauty unfold through science in this "ode to a flower" (video)

The study of the microscopic is one of the richest, most aesthetic methods of understanding the world. Lucky is the scientist who, upon seeing something beautiful, is able to see all of the tiny

To invent those we love or to see them as they are? Love in two of the movies' favorite scenes

So much has been said already, of “love” that it’s difficult to add anything, much less something new. It’s possible, though, perhaps because even if you try to pass through the sieve of all our

This app allows you to find and preserve ancient typographies

Most people, even those who are far removed from the world of design, are familiar with some type of typography and its ability to transform any text, help out dyslexics or stretch an eight page paper

The secrets of the mind-body connection

For decades medical research has recognized the existence of the placebo effect — in which the assumption that a medication will help produces actual physical improvements. In addition to this, a

The sea as infinite laboratory

Much of our thinking on the shape of the world and the universe derives from the way scientists and artists have approached these topics over time. Our fascination with the mysteries of the

Sharing and collaborating - natural movements of the creative being

We might sometimes think that artistic or creative activity is, in essence, individualistic. The Genesis of Judeo-Christian tradition portrays a God whose decision to create the world is as vehement

John Malkovich becomes David Lynch (and other characters)

John Malkovich and David Lynch are, respectively, the actor and film director who’ve implicitly or explicitly addressed the issues of identity and its porous barriers through numerous projects. Now