Your suffering can be that exquisite raw material you need in order to create

Francis Bacon reflects on the role of suffering in the creation of truly great works of art.

The notion of the artist as a being tortured by his own misfortune has been culturally misinterpreted to the point of becoming toxic. It is generally believed, especially among art students or pop ideologies, that suffering is required to create substantial works of art, and therefore tragic figures (as human as us) are idealized for all the wrong reasons. Something valuable is lost in those mythologies. Underneath the apparent “romantic” pathology of disturbed artists, there is a vital dialogue between creativity and the role of misfortune.

It is true that some of the most moving works of all time have been born from that profound place, but their true value resides in courage. Using creativity, the artist could transform a feeling into a means of communication. Thus, courage before pain, and not pain itself, is what transcends. And sadness, or pain, is one of the most fertile places that exist in us; it is because of them that we become transformed.

Francis Bacon (1909 – 1992), known for his overly violent imagery, charged with anxiety and terror, used to say that “The feelings of desperation and unhappiness are more useful to an artist than the feeling of contentment, because desperation and unhappiness stretch your whole sensibility.”

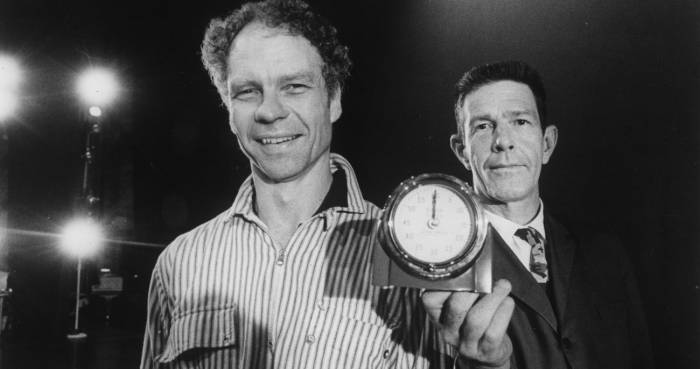

Suffering is called “the ancient food of heroes” because, like clay, it is a malleable material for creation. According to Bacon, the artist must take what he is given and transmute it. In an interview with John Gruen, the prominent art critic, Bacon delves into the correspondence between human creativity and torment.

"I think that life is violent and most people turn away from that side of it in an attempt to live a life that is screened. But I think they are merely fooling themselves. I mean, the act of birth is a violent thing, and the act of death is a violent thing. And, as you surely have observed, the very act of living is violent. For example, there is self-violence in the fact that I drink much too much. But I feel ever so strongly that an artist must learn to be nourished by his passions and by his despairs. These things alter an artist whether for the good or for the better or the worse. It must alter him. The feelings of desperation and unhappiness are more useful to an artist than the feeling of contentment, because desperation and unhappiness stretch your whole sensibility."

Who better than Bacon, a master translator of emotional terror’s inventory, to give account of the importance of facing, and be nurtured by, human passions? Part of the great power of his paintings, as H. Potter Abbot explains in this wonderful essay, comes from his rejection to satisfy the desire for narrative that his work awakens in us. “The experience of indeterminacy, of wanting to know and not being allowed to know, is itself a kind of pain and dimly echoes the terrible pain that the pictures express,” he observes. It is precisely that conveying capacity which makes everything (literally) worth the pain. In Bacon’s work we want to understand the pain, even if it hurts us. We want narrative, but the painter frustrates it immediately. On the one hand he fosters it —think about his triptychs or series that evoke movement, sequence—, and on the other he annuls it: nothing is clear in that movement.

Upon this, Bacon himself said that “The artist’s job is not to be clear, to be heard fully and understood, or to even be liked. The job of an artist is to deepen the mystery within each person that crosses their path so much that they have no choice but to give up shallowness.”

But, returning to the overly romanticized suffering of the hero, Bacon, with astounding self-awareness, contemplates the relationship between misery and creativity, in its widest sense. He cuts, with one stroke, the idealization of suffering (“suffering for the sake of suffering”) and reminds us that, after all, emotions are material and the artist is an artifice. “You must understand”, he said, “life is nothing unless you make something of it.”

"Of course I suffer. Who doesn’t? But I don’t feel I’ve become a better artist because of my suffering, but because of my willpower, and the way I worked on myself. There is a connection between one’s life and one’s work — and yet, at the same time, there isn’t. Because, after all, art is artifice, which one tends to forget. If one could make out of one’s life one’s work, then the connection has been achieved. In a sense, I could say that I have painted my own life. I’ve painted my own life’s story in my own work — but only in a sense. I think very few people have a natural feeling for painting, and so, of course, they naturally think that the painting is an expression of the artist’s mood. But it rarely is. Very often he may be in greatest despair and be painting his happiest paintings."

Related Articles

Pictorial spiritism (a woman's drawings guided by a spirit)

There are numerous examples in the history of self-taught artists which suggest an interrogation of that which we take for granted within the universe of art. Such was the case with figures like

Astounding fairytale illustrations from Japan

Fairy tales tribal stories— are more than childish tales. Such fictions, the characters of which inhabit our earliest memories, aren’t just literary works with an aesthetic and pleasant purpose. They

A cinematic poem and an ode to water: its rhythms, shapes and textures

Here lies One Whose Name was writ in Water. - John Keats Without water the equation of life, at least life as we know it, would be impossible. A growing hypothesis holds that water, including the

Watch beauty unfold through science in this "ode to a flower" (video)

The study of the microscopic is one of the richest, most aesthetic methods of understanding the world. Lucky is the scientist who, upon seeing something beautiful, is able to see all of the tiny

To invent those we love or to see them as they are? Love in two of the movies' favorite scenes

So much has been said already, of “love” that it’s difficult to add anything, much less something new. It’s possible, though, perhaps because even if you try to pass through the sieve of all our

This app allows you to find and preserve ancient typographies

Most people, even those who are far removed from the world of design, are familiar with some type of typography and its ability to transform any text, help out dyslexics or stretch an eight page paper

The secrets of the mind-body connection

For decades medical research has recognized the existence of the placebo effect — in which the assumption that a medication will help produces actual physical improvements. In addition to this, a

The sea as infinite laboratory

Much of our thinking on the shape of the world and the universe derives from the way scientists and artists have approached these topics over time. Our fascination with the mysteries of the

Sharing and collaborating - natural movements of the creative being

We might sometimes think that artistic or creative activity is, in essence, individualistic. The Genesis of Judeo-Christian tradition portrays a God whose decision to create the world is as vehement

John Malkovich becomes David Lynch (and other characters)

John Malkovich and David Lynch are, respectively, the actor and film director who’ve implicitly or explicitly addressed the issues of identity and its porous barriers through numerous projects. Now